The Stanford Dish

Learning to fit in with nature

Beauty is subjective — I might think your baby’s ugly — but nature is a rare universal measure.

After too much time in our concrete jungles, it’s a relief to get back to where we came from. A day or two in the mountains and my shoulders relax, my head clears.

The peak above Lake Alpine is called Inspiration Point. We hiked straight up the ridge, and at 8,000 feet it hurt to get to the top, but the view was worth it — the Sierras marching to the horizon, still with patches of snow clinging to their crags, a valley dotted with blue lakes and endless green. We sat a while in the wind, birds gossiping, chipmunks skittering.

Later, swimming in the lake, the cold water wrapped me up, pushing away any thoughts. I spotted a raptor silhouetted at the top of a large pine at the edge of the lake, high above me, keeping watch. Osprey — they circled the shallow cove next to me, folding in their wings to dive, dropping like a rock, rising with a fish in their talons. Sometimes they made it back to their treetop nest, sometimes the fish slipped away.

I watched them hunt for a while.

The Osprey’s nest, built with sticks, is part of nature’s architecture — functional, organic and exactly where it should be. Our concrete jungles don’t feel very natural, but there are signs we’re edging towards more harmony with nature.

Once we left caves, we built homes from wood like the Osprey, and if you’re lucky, you might still find some in your house to knock on. Our first house was a redwood bungalow in the foothills of Oakland. But that house was built 100 years ago and our relationship with nature continues to evolve.

Frank Lloyd Wright called it “organic architecture” when a building fit in with its natural surroundings. I first experimented with my own sense of beauty next to one of his masterpieces, built for oil heiress Aline Barnsdall.

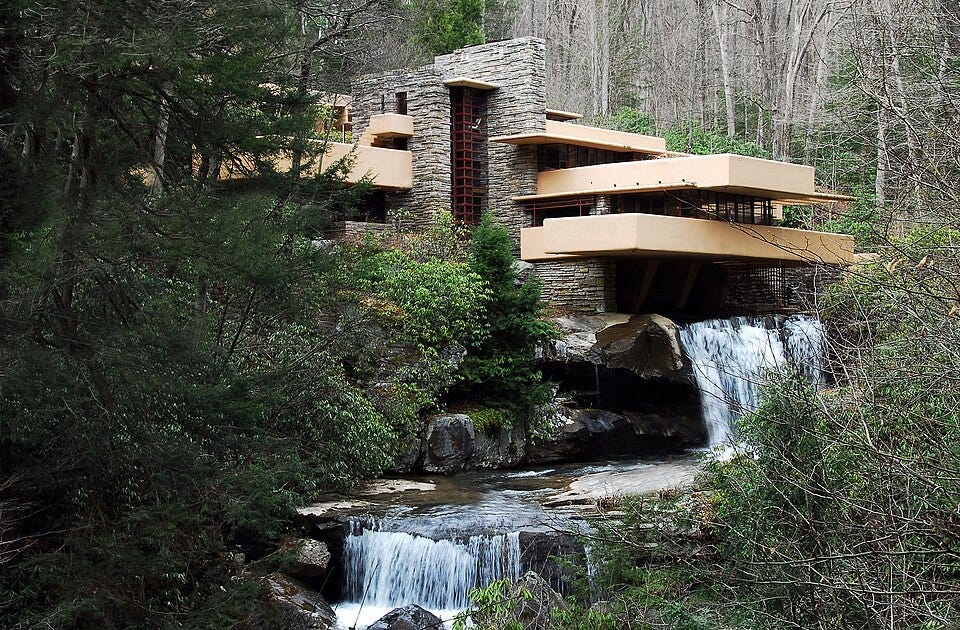

His most famous collaboration with nature is Fallingwater:

Made from local stone and wood… and reinforced concrete.

Concrete doesn’t grow on trees, but its raw ingredients — sand, limestone — are abundant. Mixed in factories that are fascinating perhaps, but certainly not beautiful in any natural way.

Growing up in Hollywood, there was a cement plant I couldn’t get enough of. Every time we’d drive by my neck would pivot, looking back as long as I could, watching the conveyor belts ratchet up, filling trucks that rumbled in and out, mixer drums tumbling.

Now that neighborhood is glassy condo blocks, each boxy and forgettable. Ironically, the Cemex plant is now the most interesting thing on the block — but not for long. They’ve lost their lease. Another condo will rise.

Some things still make my head swivel — I craned my neck last week to catch a glimpse of the Stanford Dish as we drove by. I’m always surprised to see it perched up on the hill, seemingly growing out of the grass, surrounded by California oaks — always tilted at the sky.

It feels simultaneously natural and alien.

It used to brighten my commute on the regular when I’d go down Highway 280, a blessed detour from the now Tesla-clogged grind of 101, dotted with alarmingly large billboards pitching AI. Tucked against the Santa Cruz Mountains, 280 gives you reservoirs, trees — and then, suddenly, the Dish.

A Cold War relic, it’s all function — a wire parabola built to talk to space — but its sweeping curve feels organic. It sparks the imagination.

The next day, heading out in search of mountain lakes, I saw another surprise: massive new wind turbines over the Altamont Pass.

Altamont was the world’s first big wind farm, perfectly placed where cool Pacific air meets the Central Valley’s heat, creating steady 15-mph winds. However, the windmills were raptor killers. Not Osprey, but Golden Eagles — the original windmill structures were full of perches for the Eagles to nest and the blades were deadly — low and along their hunting routes.

This new generation is different. Towering over 400 feet — taller than the tallest sequoia — with blades as long as a football field is wide, they reach higher, where the winds are stronger. The slow-looking rotation fools the eye; at the tips, speeds reach 180 mph. Twenty of these giants replaced 600 old turbines and each one powers around a thousand homes.

Like the concrete factory, like the Dish, these turbines are pure function. But their form is cleaner now, sleeker, less of an affront to the landscape. Like the osprey’s nest, they fit in with the environment instead of fighting it.

Nature sets a high bar for beauty with purpose. We don’t always clear it, but increasingly — from Fallingwater to the Stanford Dish to the wind farms of Altamont — we get closer.

I wasn't aware that the Altamont turbines had been replaced. And they're Golden Eagle friendly. Thanks for the info!

Fallingwater is sooooooo cool! What an amazing work of art and architecture. Wright has my full admiration for his creativity.

I would love to see more of this, instead of shaping things to our will. I think it's possible, but we're also big dummies, so I dunno.