Papa knew when to get out

My grandfather’s journey

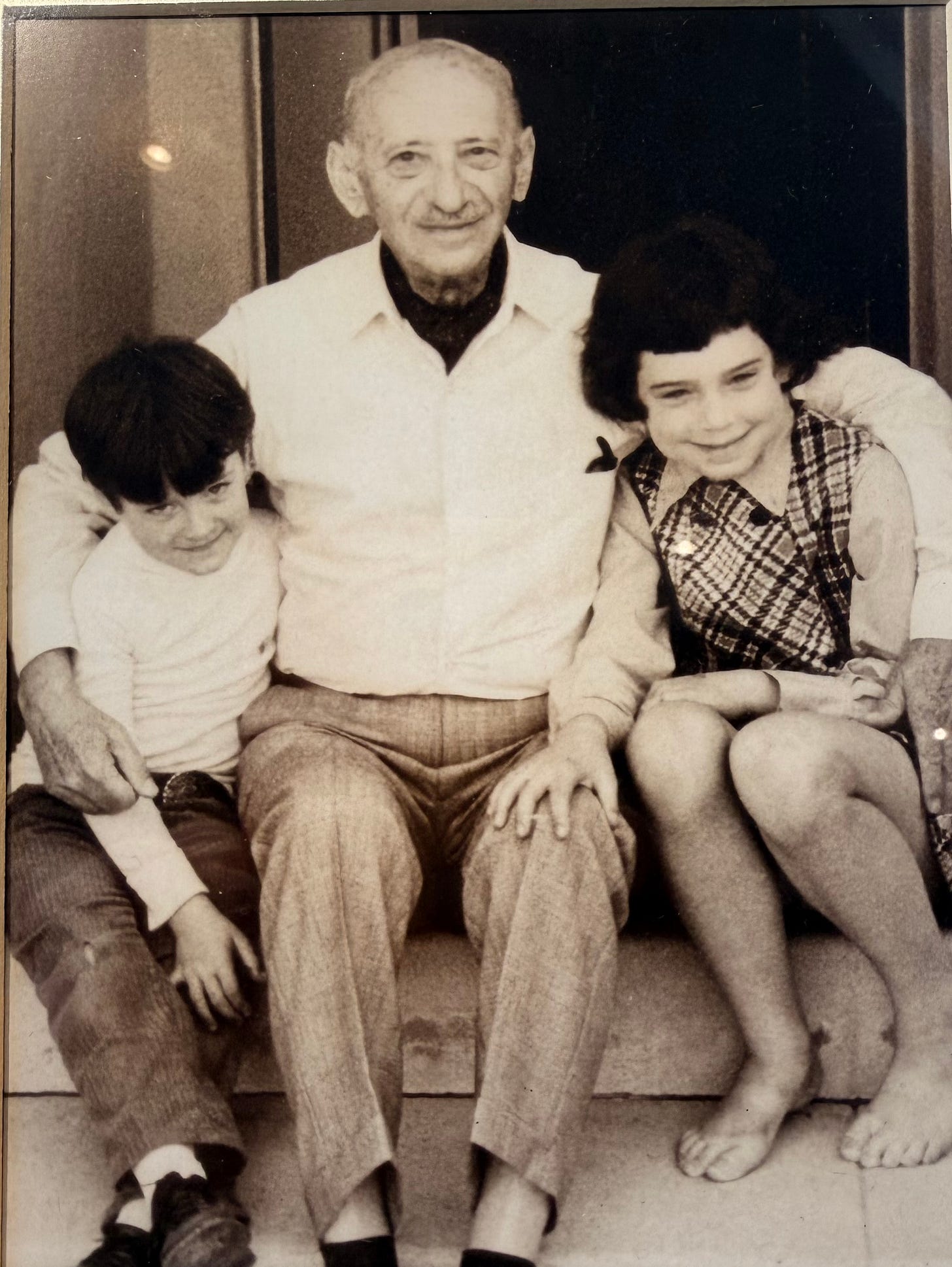

When I saw my grandpa’s little green car pull into our driveway, I rushed outside to greet him. He was my favorite adult.

I opened his car door, but he didn’t get up. He told me to get my mom. So I ran to get her. I pretty much ran everywhere back then.

Through the window, I watched the ambulance come and go. I was eight.

I miss him — all my memories of Papa are happy. He started painting when he retired in his 70s. His early work was as bad as his later work was wonderful. This one hangs in our living room.

While Papa didn’t start painting until his 70’s, he was prolific. When we were down in LA for my mom’s memorial, we pulled all his paintings out of the storage locker and took inventory — there were at least 40. We put a numbered pink sticky note on each, lining them up down the hallway. We put a picture of each one in the family chat and it was a free for all — every kid and nephew picked their favorites.

We took a big stack of paintings to the UPS store that day. They were very accommodating — the guy behind us in line — not so much.

Papa took me and my sister to the ice capades every year. We went hiking up in Griffith Park and swimming at the public pool in West Hollywood. He’d come over for lunch with the fattest deli pastrami sandwiches you could barely get your mouth around.

Once, he took me to an art fair and one of his friends painted me. It looked nothing like me, and I didn’t appreciate having to sit still for that long, but I was just happy hanging out with my Grandpa.

When JFran and I got married, we took one serious shot. I wanted to match this picture of Papa and Grandmas wedding photo.

Over the years, my happy memories have evolved into a realization that Arthur the young father, managed to extract his family from Vienna and the Nazis, over to safety in the US. As he watched his home city and country devolve into fascism under the Nazis, fearful for his family, and most of all my mother, he took action.

I can’t imagine how he came to the decision to put his only 12 year old daughter on a train — by herself — to unknown strangers and fate in far away England.

Of course it was the right move. I wrote about my mom’s escape and subsequent journey in The Wandering Jew.

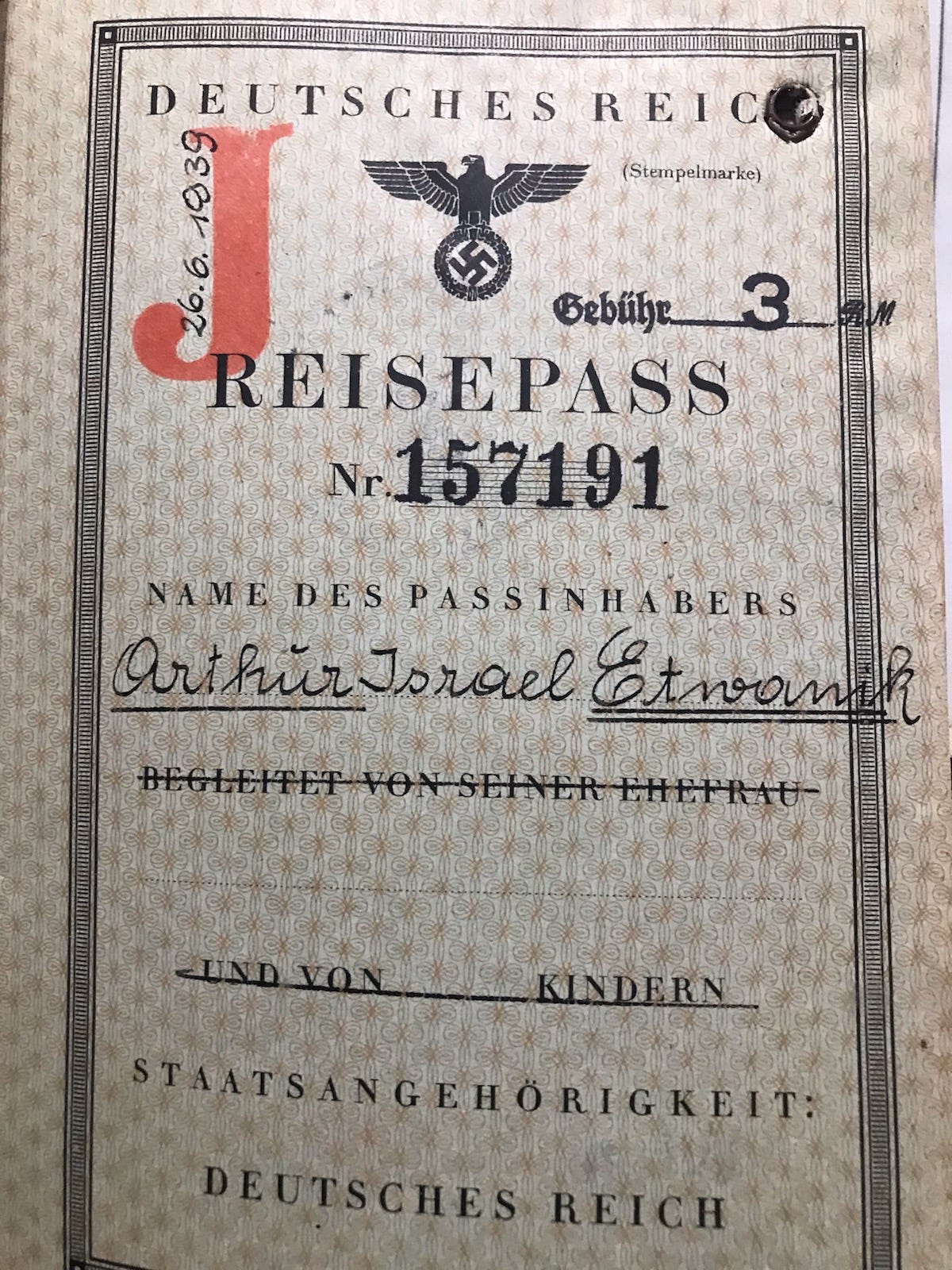

In Yom Hashoa I wrote about how Jews commemorate the Holocaust. That article has a picture of my mom with her parents before she was forced to flee. It also has this picture of Arthur’s passport:

But other than my happy memories, now framed by an understanding of the Holocaust, what did I really know about my Grandfather? Family lore was that long before he was my Papa, Arthur Israel Etwanik, was a WWI war hero where he made friends that would later help him escape the Nazis.

Perhaps this was true, but there had to be more to the story. How did he get to America? Six million Jews never made it out.

A few weeks ago, unexpectedly, a big piece of Papas story fell into my lap. Sitting in a meeting for the Holocaust Story Project, I was listening as a friend of the groups mom told her story. Her mom Hanni is 95 and was visiting from Boston.

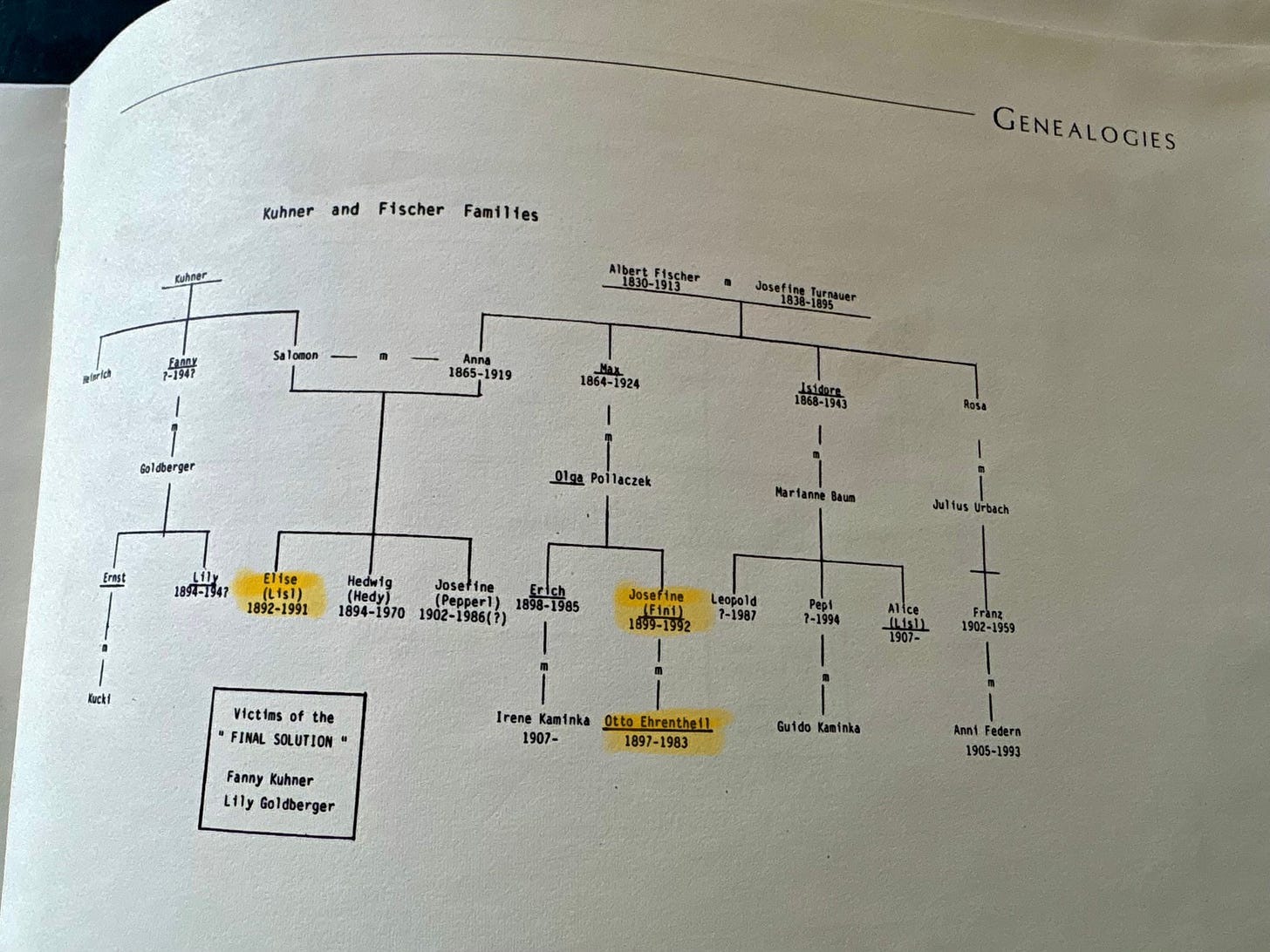

As I listened to Hanni, I was struck by how much her story sounded like my mom’s. Early life in Vienna surrounded by a loving extended family before it all came crashing down. Hanni’s accent reminds me of my Grandma. Hanni’s dad Otto was a Doctor in Vienna, and he managed to get his family out early.

Otto had a friend from medical school in Boston that sponsored his Visa into the US. Once settled, Otto began getting letters from other families trapped in Europe. Otto helped over twenty of those families find sponsors in the US. Hanni explained how her sister Susi had compiled all the letters written to her father into an anthology called Dear Otto.

When I heard Dear Otto, I sat up straight. I have that book. I blurted that out, startling Hanni. My mother gave me and my sister each a copy. At the time I didn’t realize the significance and had only glanced through it before sticking it on a shelf. I found the book and called my sister. 1

Hanni is my cousin! It was through her father Otto, that my Grandpa Arthur found a sponsor in Boston.

The story gets crazier — Hanni’s daughter who had brought her to our meeting —lives not a stones throw from my in-laws. Now I have a local cousin.

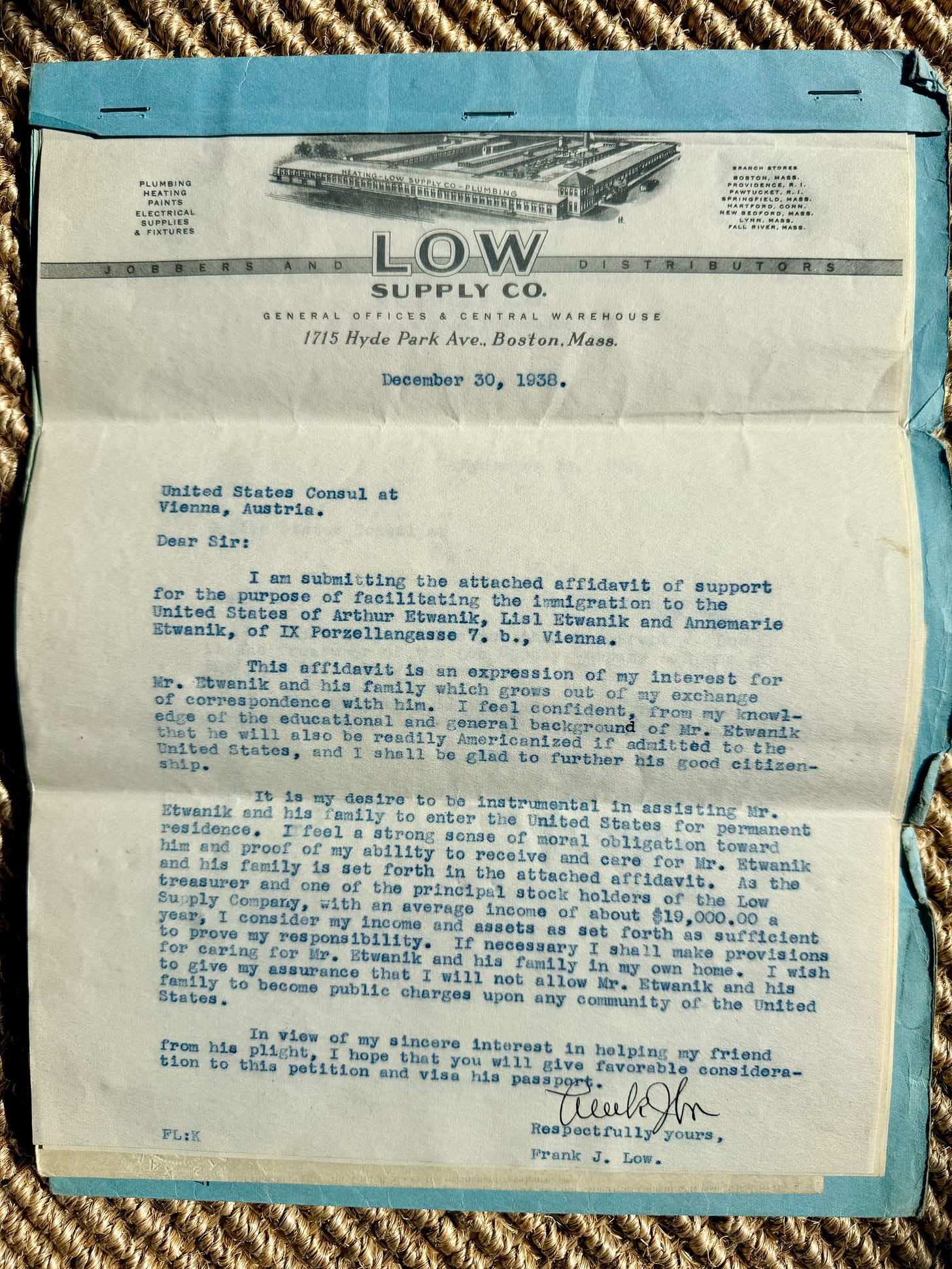

This is the cover letter of the affidavit from an officer of the Low Supply Company in Boston sponsoring my Grandpa so he could escape:

Hanni remembers my mom, Grandma and Grandpa from their time together in Boston. I told Hanni about our planned trip to clear out my parents storage locker, promising to share anything new that I found. The next morning we flew down to LA.

I still had a lot of questions about how my grandpa and grandma escaped, and I wondered if I’d find anything in the storage locker to fill in the story. I rented the biggest SUV I could find, but it wasn’t big enough. There was more stuff crammed into that storage locker than I’d expected. At the very back — under a thick layer of dust — was a stack of boxes my sister had packed up from my Grandmas house in the 80’s.

Some antique and some not so antique chairs were sacrificed to make room for all the boxes, and with the car completely stuffed, we started to drive back.

Nearly home, I hit the brakes at the Richmond Bridge toll plaza and a box precariously perched on top of the stack in the back seat flew out spilling onto JFran’s lap. A cigar box whizzed by her head onto the floor, spilling out all kinds of stuff including my grandpa’s WWI medals.

We collected them all once we got home — the medals confirm that Papa had served with honor in WWI, becoming an officer.

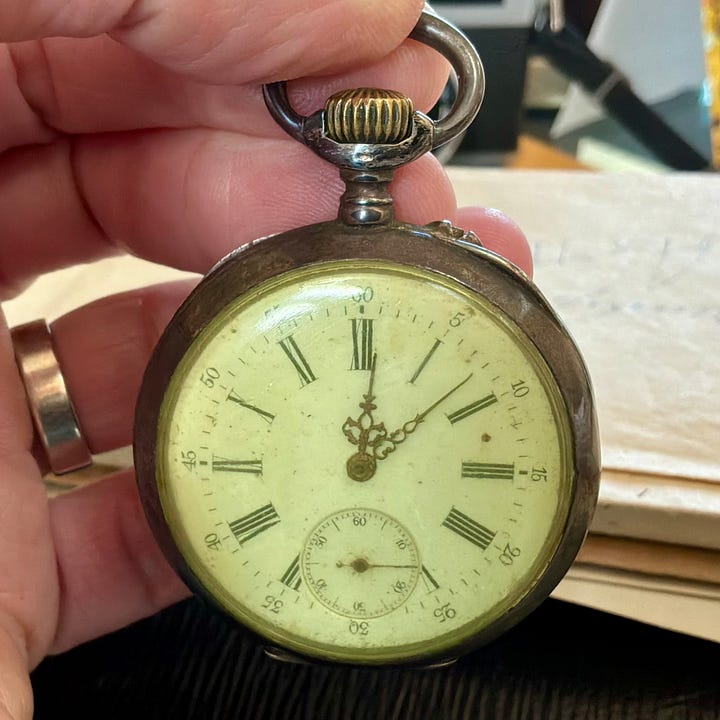

Something else came flying out of that cigar box: a pocket watch from the 1910s. Young Arthur must have carried this watch with him during the war. The face is glass, scratched and worn from use. It’s heavy and silver. I wound it and set it; it still tells time.

A reliable watch was standard issue during WWI. Timekeeping was essential.

I have another watch of Arthur’s that he had given my dad, and that my dad had passed on to me. It’s gold and lighter and fancier, and it dates later, in the 1920s. I imagine an older Arthur carrying this one after WWI when he was a proud dad — married and working in Vienna.

While I was done with a first draft of this story, I couldn’t resist grabbing another box from the pile in the garage. This box was full of letters and folders from Austria. The top folder says, in my mom’s neat handwriting: WW I. Beneath that, a small journal: War Diary Aug - Nov 1914. Lots more.

It’s all in German, and honestly a bit overwhelming.

Inside the big box, was a small wooden box of my Grandma’s, filled with letters from my Grandpa. Most are handwritten, but I found a few that were typed. These are dated June 1939, around six months after my mom left Vienna for London on the Kindertransport.

I translated them. My grandfather had left Vienna leaving my grandma behind to secure visas. He traveled with his younger brother and his family to get them out. The letters are hard to read. Arthur’s father died while he was away and he is distraught. His niece gets terribly ill on a long boat ride over and they have to leave her behind in a hospital.

It’s hard for me to exactly trace Arthur’s route, but what is clear is that he’s desperately trying to figure out a way to escape Europe for the US.

While in London he is able to see my mom. Here’s the passage from the letter describing their reunion:

Our stay in London fulfilled its purpose … and we were together with Herta and above all with Anne. I find this child so charming, so dear, and so sensible. She already seems to speak English particularly well; during the first hours it always took effort for her to say everything in German — again and again she mixed everything with English words — and I often had to ask her to speak English more slowly so that I could understand her.

At our request by telephone, Anne was sent to London and was completely unprepared for the fact that she would be coming to us. But she was extraordinarily happy with us, slept in our room, and the children truly delighted in one another. Naturally, I tried to draw out of Anne whether she was completely content, which I did not entirely succeed in doing. But she looks very well, seems very grown-up to us, healthy, with a good appetite and very cheerful.

Arthur would leave his daughter, my mother, Anne in London for another six months so another Jewish child could get out under the quotas, only sending for her once they had settled in Boston.

I cannot imagine how exhausting and emotional this must have been. Of course that’s why so many stayed and died. Papa had the foresight to know when to get out, the support of friends and the fortitude to see it through.

Things are getting weird in our country. I don’t like it. We all see it, and the drumbeat of change picks up, bit by bit, year over year.

I hung Papa’s soldiers watch at my desk. I try to remember to wind it every day, it’s important to keep track of the time.

I often wonder how Papa knew when to get out. Would I know?

She gave it to us along with a VHS copy of Into the Arms of Strangers, a documentary about the Kindertransport.

What an incredible story! I love everything about it. I also wonder how will we know when it's time to leave? And where will we go? And can we go together, please?

Thank you for this, Andrew.

I mean it. These stories disappear if someone doesn't do the work of preserving them, translating them, writing them down.

You're keeping Arthur visible - not just as a survivor but as a grandfather, painter, father who made impossible choices. I appreciate the photos most of all.

Happy Friday to you!