Single-source

Ancestry results, family secrets, and the messy fight over a company built on spit.

When 23andMe used the mapping of the human genome to provide DNA test kits to consumers, the buzz was palpable. 23andMe was Time’s 2008 Invention of the Year, and the news was full of “Not Parent Expected1” stories of kids figuring out their dad wasn’t their dad or their siblings weren’t, yep you guessed it — actually related to them.

In 2003, after 13 years of work, the Human Genome Project published a complete reference of our DNA made up of 3.2 billion base pairs. Based on that work, a simplified mapping technique called SNP was standardized where only a fraction of a person’s DNA needs to be measured to reveal ancestry breakdowns, relative matches, and trait/health summaries.

Anne Wojcicki seized on the development of the relatively inexpensive SNP tests in 2006 to create the first cost-effective individual genetic test for 23andMe. The market was untapped — what’s more exciting than finding out where you came from?

Anne has a background in biotech, but her innovations at 23andMe were more about the business model than the science or technology.

23andMe’s $99 test went viral over the holidays. One story I recall was a mom freaking out when one of her kids gifted tests to the whole family. On Christmas Day she confessed that her husband wasn’t the genetic patriarch everyone assumed. It ruined the holiday.

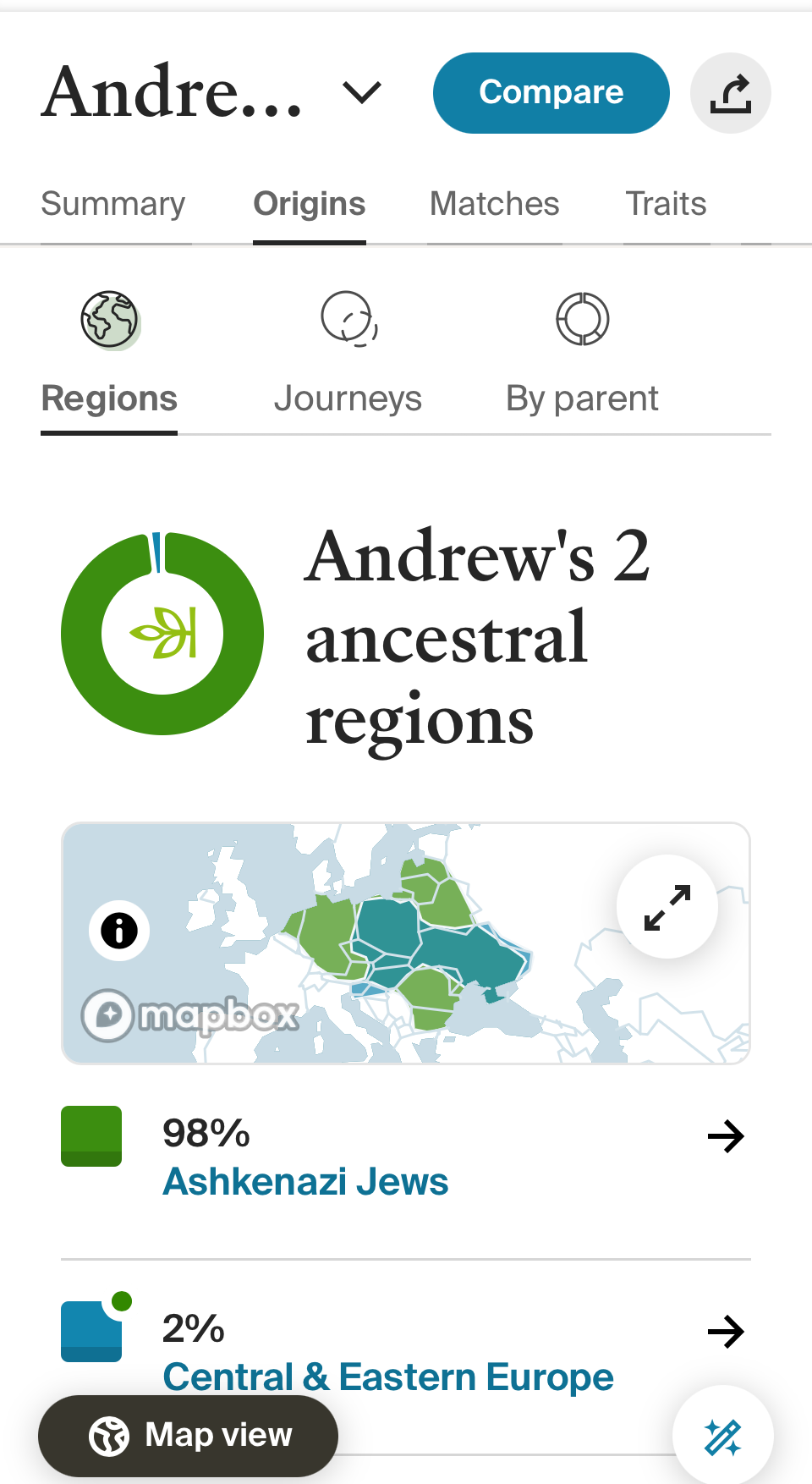

So when I sent my Ancestry DNA test in last month, I was looking for drama. I should’ve known better. After all, I wrote up my mom and dad’s origin stories on their respective birthdays earlier this summer and my mom’s parents are both from Vienna going back generations, and my dad’s parents are both from the same region in Eastern Europe (now Poland and Russia) going back generations.

I’m 98% Ashkenazi Jew:

Jews were first dispersed from our ancestral homeland in Israel back in Babylonian times and the Jewish Diaspora has subsequently spread to North Africa and Europe and most recently the Americas. Ashkenazi is a biblical name for Germany, referring to the Jews who moved West from Israel through the Mediterranean and then North to Germany, eventually migrating East into Poland, Czechoslovakia and Russia.

In 2008 I was working in the Czech Republic and I passed for a local. I wore a black leather jacket, a beanie and a scowl and I rode the train into town like I owned it. As long as I didn’t open my mouth, no one suspected I wasn’t born and raised in Eastern Europe.

Ashkenazi Jews are the largest branch of the Jewish Diaspora, numbering around 10 million. My Ancestry.com dashboard is now lit up with 16,000 potential relatives on my dad’s side; 18,000 on my mom’s.

While my ancestral story is pretty straightforward, the way I found it out — through 23andMe’s commercialization of DNA testing — is full of drama.

Anne founded 23andMe while she was dating Google co-founder Sergey Brin. Her father was Polish and her mother was of Russian Jewish descent, making her Ashkenazi Jewish — just like my dad’s family.

Anne married Sergey, who I wrote about a few years ago now, as the face of one of the first wearable tech products — Google Glass. Glass was a monumental flop, and that TechTale includes how Sergey strayed from Anne in the process, having an affair with Google Glass marketing manager Amanda Rosenberg.

Anne launched 23andMe early in their marriage, while Brin was working on Google Glass. Ironically, their subsequent split is rumored to have started with Brin’s 23andMe test result showing he had a genetic disposition for Parkinson’s disease. Initially Brin took that to mean he had 10 good years left. Soon after, his affair surfaced, Anne and Sergey separated.

Family ties and Silicon Valley connections weave together the story of 23andMe. Anne’s older sister Susan let Sergey and Larry set up Google’s first office in her garage which is how they met2.

Through it all, Anne aggressively raised money. Sergey personally put in $12 million, and they pulled in more from Google Ventures and friends-and-family rounds. Celebrities chipped in — including Harvey Weinstein — with 23andMe hosting “spit parties” to collect DNA samples.

By 2013, 23andMe was flying high and Anne landed the cover of Fast Company:

Immediately after this article, the FDA aggressively came after the medical reports the company shared with consumers. The FDA fight dogged the company for several years but they got through it, and in 2021 23andMe went public, shooting up to a $6 billion valuation. But the fad had passed and revenue was flat. 23andMe’s valuation dropped steadily over the next couple of years, losing 80% of its value.

In October 2023, 23andMe disclosed a massive security breach. Ultimately it was revealed that millions of accounts — nearly half of their user base — were leaked with raw genetic data posted on criminal forums including subsets labeled “Ashkenazi” and “Chinese.” The stock dropped into penny territory.

Personal and civil lawsuits mounted, resulting in a $50 million settlement. Earlier this year the stock became essentially worthless and 23andMe filed for bankruptcy. Anne’s entire board resigned, unhappy with the company’s direction.

Regeneron was the leading bid for 23andMe’s assets at $200 million. Regeneron is a pharma company, and they wanted the user data for clinical drug development. Anne fought to win back her company — her legacy. She formed a non-profit shell company called TTAM (the letters of 23andMe…) and with an unnamed Fortune 500 company backing her, she won back the company with a $300 million counteroffer.

Anne is a complex character — obviously driven, but to what end? The market she created has fundamentally changed and is now full of competitors like the DNA test I used from Ancestry.com. Ancestry hooks the test into their subscription services. A fundamental problem with 23andMe’s business model is they sell a product you only need once in your lifetime. It’s hard to sustain any business without repeat customers.

The tech has also changed. 23andMe’s dataset is perfect to train machine learning models (AI) for gene-trait correlations and new drugs. This is what Regeneron wanted and back in 2018 23andMe had a partnership with GSK for the same reason. Earlier this year, Novo Nordisk — the Danish pharma giant and maker of the weight loss drug Ozempic — inked a nearly $1B deal with AI research firm Deep Apple.

This is the future of the industry, but using my genetic data feels a bit squirrely. Now that I know my ancestral secrets, I’m considering deleting my account and data. While I have no issue with anonymized data used for new treatments, given 23andMe’s story I’m not sure I need my genetic makeup lying around for someone to snitch.

What do you think — am I being paranoid?

NPE forums are now prevalent online.

Susan subsequently joined Google where she was a longtime exec, ultimately CEO of YouTube. She left in 2023 after revealing she had lung cancer, passing in 2024.

This was a great, informative read. Well written and detailed as always. But as far as the privacy issue goes; I believe it’s a thing of the past for all of us, particularly after the unconscionable personal data grab by DOGE earlier this year. My opinion.

I'm definitely paranoid. Big brother watching. Skynet becoming self-aware. I need to delete my account, but I just haven't moved forward.