The Great American AI Buildout

It’s the biggest thing we’ve ever done

The labor broker was really getting into his pitch when he locked onto Shi Qiang. It was monsoon season in Taishan, and the air lay thick and heavy in the small room. Shi stood off to the side, clustered with a group of friends. He listened intently, as the man told of a journey overseas to America, to Gam Saan — Gold Mountain — where he could make more money in one year than five years in Guangdong.

Southern China was in collapse. The Taiping Rebellion had emptied villages, floods and droughts had ruined rice crops, and the tax demands of a weakening Qing dynasty were a final crushing blow. Shi’s family had lost two harvests in a row. His parents were getting older; his younger sister wanted to go to school. At 23, he knew he needed to find a different way. Qiang means ‘formidable’ (强) — so, resolutely he signed the broker’s contract.

The Central Pacific Railroad would front his passage; he would repay it on a $30 a month salary to build a great railroad in America.

Shi said his last goodbye to his dad in Hong Kong, and turned his back — filled with equal parts excitement and anxiety — joining the crowd heading up a ramp onto the steamship that would take two months edging across the massive Pacific Ocean to San Francisco.

Knees weak from 8 weeks at sea, the final leg of Shi’s journey started in a dim boxcar packed with dozens of other Taishanese men climbing up into the Sierras. When the tracks ended at Cisco Grove, they climbed the last ten miles on foot — up frozen trails, past wagon teams and powder carts — until the black mouth of Tunnel Six came into view.

Shi’s journey around the world and up the mountain echoes again — unexpectedly — 150 years later.

Shi’s job was Tunnel Six. It cut beneath Donner Pass, a route surveyor Theodore Judah1 chose as the only viable spot to cross the Sierra with a manageable grade and a relatively straight shot east from Sacramento — even though it meant drilling nearly two thousand feet through solid granite. Just twenty years earlier, the Donner Party horrifically perished in this same spot. Now it was the key to a transcontinental dream.

Shi spent two brutal years carving that tunnel: drilling, blasting, and hauling rock through 44 winter storms, snow drifts 20 feet deep, living in makeshift snow tunnels hundreds of feet long. He bunked in cutouts off the tunnels that had to be rebuilt after each storm. He saw friends die in blasts and collapses.

After fifteen months of drilling from both sides, the crews finally met in the middle. It was November 1867 and Shi was there watching as a small circle of daylight appeared, filtering brighter as the dust settled. By the summer of 1868, trains were crossing the Sierra through Tunnel Six. A year later, at Promontory Summit in Utah, Central Pacific’s Jupiter and Union Pacific’s No. 119 — two massive 30 ton locomotives — met to complete the transcontinental line. Chinese workers — 90% of the labor force in the mountains — were excluded from the golden spike2 photo and ceremony broadcast across the nation.

Six months is what it used to take — best case — to get from New York City to San Francisco. Now you could get there in 7 days.

Shi’s story is one of thousands that built the railroads, unifying a nation still finding its footing after the civil war. Tunnel Six represented the pinnacle of American grit ever pushing against the frontier, yet it was but one tunnel out of 15 needed to cross the Sierras.

Connecting the coasts triggered an even more massive buildout, and by the 1890s, tens of thousands of miles of new track were added each year, extending the nervous system of a new industrial economy across the continent.

America’s industrial might poured into the rails with singular focus: ironworks of molten metal, mills of massive machines, mines lugging ore from the deep, ships off-loading onto sprawling docks, forests felled, quarries blasted, telegraph wire strung from pole to pole adjacent every rail spur.

By 1900, 200,000 miles of track had been laid across the country at a cost of what would be nearly $1 trillion dollars today. America built on top of this base for the next 125 years, and now we are building a new platform.

The railroad buildout was the largest collective investment America ever made in peacetime — until AI.

Software grew from a niche industry in the 1980s into today’s economic backbone — our modern rails. Computing became the infrastructure every business runs on, setting the stage for what’s happening now.

When I started out in software, the business model was simple and … simply amazing. Windows and its successors cost nearly nothing to produce. Media (floppies, CDs), manuals and distribution cost pennies — the margin on selling a copy of Windows was as close to pure profit as you could get. Companies like Microsoft grew fast and they grew strong during this golden age of software,

In 2006, Amazon Web Services changed the game. It wasn’t enough to just deliver software anymore — now you had to run it. Microsoft followed Amazon’s lead and Google followed soon after, each investing heavily to build out ever larger, denser and more efficient datacenters around the globe.

The next 15 years saw increasingly aggressive infrastructure spending, winnowing out the stragglers until just the handful of tech companies that could afford to spend billions a year remained. Computing is now a core utility akin to the electrical grid, oil & gas distribution, air, rail and highway supply chains.

Next up was AI.

18 months ago, marking the rough midway point between the first release of ChatGPT and today, I covered OpenAI & Microsoft’s Stargate announcement. Since then a massive and unprecedented AI datacenter buildout has fanned out across the United States, fueling a new focus, a new AI gold mountain.

The first release of ChatGPT in 2022 was AI’s golden spike moment and it caught fire. I initially believed it would disrupt some of these established players. Heck, I wanted it to disrupt the established players. I hoped Google would falter with their search monopoly, Meta would be rocked by foundational changes in consumer interactions, Apple would be challenged by native AI devices3.

I was wrong — tech is as core to our economy and progress today as the railroads were in the 1900s and big tech is entrenched. The days when one brilliant coder could disrupt the system is over. Capital requirements hold the upstarts at bay — each of these companies has built a wide moat that protects their business.

While there are a handful of nimbler AI labs building frontier models — a bit like the Central Pacific and Union Pacific that laid the tracks across the frontier — for the most part it’s the same big tech players.

Google, Amazon, Microsoft and Meta: now with the ‘hyperscaler’ label:

Amazon goes big in Pennsylvania across multiple sites adjacent to nuclear power with a price tag of $20 billion statewide. Microsoft’s Fairwater project in Wisconsin covers 315 acres costing tens of billions4. Google takes up residence in Arkansas with their West Memphis project across over 1,000 acres and $4 billion. Finally, Meta’s Hyperion in Richland Parish, Louisiana is the biggest in raw scale covering 2,000 acres at a cost of $10 billion.

There’s more5. The smaller AI frontier labs are busy making alliances in addition to their own buildouts. For example Anthropic is working with both Google and Amazon. OpenAI makers of ChatGPT, originally aligned with Microsoft, now has the most ambitious buildout plan of all: across a partnership with Oracle and SoftBank via Stargate LLC, they are building 5 AI datacenters including Texas, New Mexico and Ohio, and plan to spend up to $500 billion by 2029.

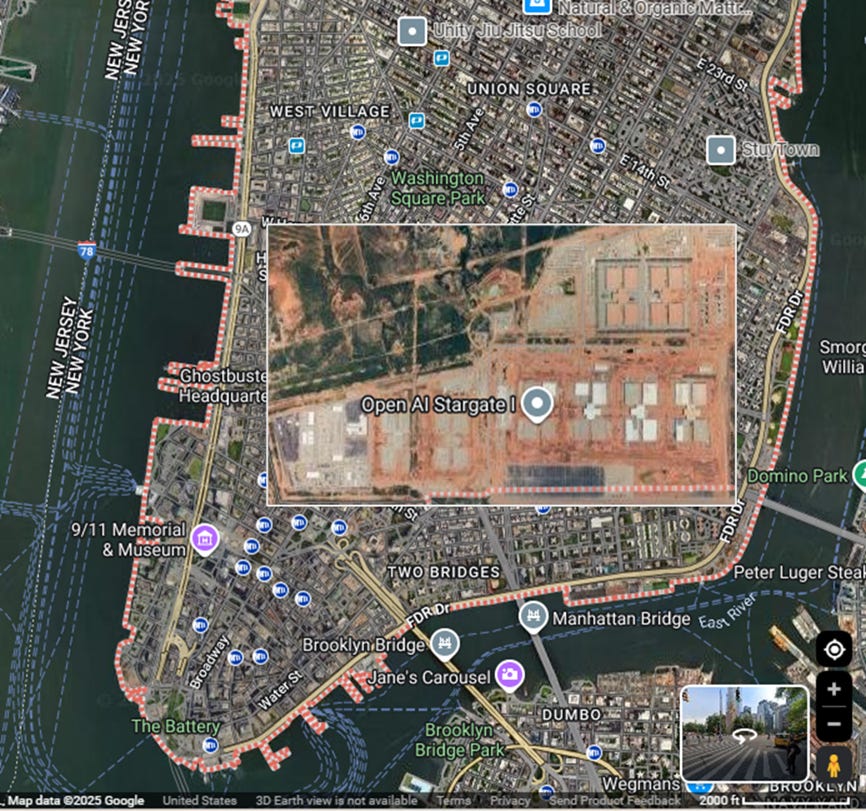

To get a sense for just how massive one of these is, here’s a visual of the first Stargate AI datacenter, just now coming online in Abilene, Texas.

Ever been to NYC? The Abilene datacenter is as big as lower Manhattan:

Meta’s Hyperion is twice as big and would cover all of Manhattan.

Building one of these takes more than grit and black powder, rails and spikes6. 200,000 tons of gear hauled in by convoy; turbines placed with towering cranes; chillers the size of houses lined up in rows; cable trays filled with hundreds of miles of fiber; and power turbines so big, you can see their heat signatures from space.

And then you replicate one building into — six, seven, or eight — until a single site becomes a city of machines.7

Why does AI need so much computing capacity? The furious debate in tech today is Compute versus Algorithm. Which will advance AI quicker? Compute is simply capacity. More datacenters mean more factory muscle to build AI models faster. Algorithm on the other hand is smarts — new programming techniques that improve model cognition while reducing the time needed to train them.

Well, it turns out you need both. Compute gets you there faster and leads to the development of novel algorithms. Combining the two leads to exponential growth.

What can we expect from new generations of AI already arising from this massive buildout? AI has quickly become synonymous with both good and bad; accordingly, AI will get simultaneously much better and much worse.

In a year, you will no longer think it’s weird to talk to a computer to get things done and amazing things like real-time language translation will become commonplace.

In two years, every information driven industry from law to engineering to medicine will run with dramatically improved efficiency and outcomes on AI. Weather forecasting, earthquake modeling, addressing climate change, reducing pesticide use, on and on.

In three years, scale robotics will finally meet scale AI with mass market robots from household help to civil service. After that? It’s the stuff of science fiction.

Bad? Sure, AI will continue to challenge us with fakes and slop, with ever evil-er social media, and societal challenges as we deal with the increasing and unintended consequences of personal interactions with computers that think.8

Locomotives are fascinating, yet they aren’t the hero of the railroads. It’s what rail connectivity did for the nation. AI models are fascinating, be it OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Google’s Gemini or Anthropic’s Claude, but they aren’t the hero either. In the end, these models will become a footnote like the CPRR’s Jupiter — what will last are the changes they will bring to our lives and to our planet.

Shi Qiang was one of over 12,000 Chinese immigrants that built Tunnel Six. However, their contributions were never recognized. After the great rail buildout, work tapered off. In a now recognizable pattern of protectionism, the US turned against Chinese workers, passing the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. Shi could no longer leave the US and hope to return, and he never saw his parents or his sister again.

However, the money he sent back kept them going, and eventually he made his way back to San Francisco where he met and married a merchant’s daughter in a growing Chinatown.

Shi’s great-great-great-granddaughter is now an AI researcher at OpenAI’s San Francisco headquarters. Back on the other side of the world, China is rushing into an AI future with their own aggressive investment cycle, to the tune of $70 billion. While China lags US AI capabilities, they are working hard to close the gap.

This time, they will undoubtedly be in the picture.

While Tunnel Six now sits abandoned, train spotting on the summit is still a blast — especially in the dead of winter when the snow plow train blows over the summit.

Current score: Google research invented the Transformer in 2017 - the seminal breakthrough that enabled Large Language Models. But they sat on it, afraid to disrupt the money printing machine that is search. Just earlier this week they released their latest model, Gemini 3 and just like that they’re back in the game. Meta is on its heels the most of these three as they inject AI into their social feeds in the most embarrassing ways thrashing about, looking for a hit. Apple I wrote a bit on recently and I expect the new Siri to be pretty good and they are on their way. New devices TBD (rumors are Tim Cook will retire as CEO next year…).

Microsoft just made up a new word for this site: AI Super Factory. Inside Microsoft’s new AI Super Factory

In a nod to how creative the quest for capacity is getting, in Am I Hot or Not, I wrote about Relativity Space and CEO Eric Schmidt’s aspiration of building datacenters in space. While it was a ridiculous reach just three months ago, last week Google went public with their plans to launch a space datacenter: Project Suncatcher Moonshot.

While building a Chip Fab is more complicated than building a datacenter, they are adjacent. For more check, out Chip Wars I wrote on this last year.

If you want to see more of what all goes into building one of these, including a drone flyover of the whole site, check out this article and watch the video: Stargate: A Citrini Field Trip

I recently read Harlan Ellison’s I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream. AM is one pissed off machine; let’s hope it doesn’t get that bad.

People fear what they don't understand- the 19th century Chinese, homosexuality, AI. Too much Terminator

I've been reading articles about the power needed too keep these massive data centers going. The current administration's promotion and use of coal and other fossil fields for power, can not supply enough power needed for these data centers. China is building up solar and wind energy that can support the power that is needed now and in the future. America will get left behind unless they change their thinking, and policies on how to increase the energy that will be needed. These centers also use a massive amount of water.

On a side note, I also read how utility companies around the country are charging homeowners more to support the data centers in their communities. Those big tech companies worth billions should bring money into a community, not taking it away to make them even richer.

That's my old man rant for the day.